Debt and Deleveraging: Did the U.S. Overcome the Debt Crisis? Light at the End of the Tunnel Anywhere? Five-Pronged Solution

Mish Moved to MishTalk.Com Click to Visit.

Citing the latest report on "Debt and Deleveraging" by the McKinsey Global Institute, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard proclaims America overcomes the debt crisis as Britain sinks deeper into the swamp.

Britain has sunk deeper into debt. Three years after bubble burst, the UK has barely begun to tackle the crushing burden left by Gordon Brown. The contrast with the United States is frankly shocking.US Did Not Overcome Debt Crisis

US debt is already lower than Spain (363pc), France (346pc), or Italy (314pc), and may undercut Germany (278pc) before long -- given the refusal of the European Central Bank to offset fiscal contraction with monetary stimulus.

One is tempted to ask what all the fuss was about in the US. The debt of financial institutions is just 40pc, compared to the UK (219pc), Japan (120pc), France (97pc), Germany (87pc) and Italy (76pc). Bank debt has dropped from $8 trillion to $6.1 trillion -- accelerated by the Lehman collapse -- as lenders rely more on old-fashioned deposits.

In hindsight, the US property boom was remarkably modest compared to what happened in Spain, or what is happening now in China now where the house price to income ratio in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen is near 18. America’s ratio peaked at 5.1 and is already back to its modern era average of three. The excesses have been unwound.

Personally, I am coming to the conclusion that the US crisis in 2008-2009 was largely a case of botched monetary policy and could easily have been avoided. The growth of M3 money -- which the Fed stopped tracking thanks to a young Ben Bernanke -- was allowed to balloon in the bubble, then collapse in 2008.

There is a big difference between alleged "light at the end of the tunnel" and "America Overcomes Debt Crisis" as Pritchard claims. US consumers may be one-third of the way through, but US debt-to-GDP ratios are low only because unsustainable government spending has taken up the slack.

The US has not started government debt deleveraging and until that is nearly finished there will not be light at the end of the tunnel, let alone the end of the crisis. Optimistically, the best one can possibly assert is one can possibly see light at the end of the "consumer tunnel". The government tunnel immediately follows.

Moreover, one should not be "tempted to ask what all the fuss was about in the US". Just because other nations are worse, does not mean the US had no problem.

Five-Pronged Solution

US monetary policy and ECB monetary policy is partially to blame for these crises as Pritchard says. Reckless fiscal policies by governments everywhere is another part of the problem. The five-pronged solution which Pritchard does not mention is ...

- Get rid of the central banks

- Get rid of fractional reserve lending

- Return to a gold standard.

- Minimize governments

- Embrace free market policies

Please see Hugo Salinas Price and Michael Pettis on the Trade Imbalance Dilemma; Gold's Honest Discipline Revisited for a discussion of how a gold standard can fix trade imbalances.

Eurozone Structural Problems

The European crisis now was foreseen in advance by many, including Pritchard.

Certainly the ECB's "one size fits Germany" interest rate policy fueled the property bubbles in Spain and Ireland, as well as imbalances in Italy, Greece, and Portugal.

Unlike the US, the eurozone has the structural additional problem of being a monetary union without a fiscal union. Not one such currency union in history has ever survived.

Bailing out Greece and Portugal and Ireland will not fix structural problems including the ECB's "one size fits all" interest rate dilemma.

Debt and Deleveraging

Here are some excerpts from the McKinsey Global Institute PDF.

Click on any chart below for a sharper image.

Executive SummaryThat last sentence, coupled with the fact that consumer deleveraging is only 1/3 finished is precisely why the headline title by Pritchard that "America Overcomes the Debt Crisis ..." is quite inaccurate.

The deleveraging process that began in 2008 is proving to be long and painful, just as historical experience suggested it would be. Two years ago, the McKinsey Global Institute published a report that examined the global credit bubble and provided in-depth analysis of the 32 episodes of debt reduction following financial crises since the 1930s. The eurozone’s debt crisis is just the latest reminder of how damaging the consequences are when countries have too much debt and too little growth.

In this report, we revisit the world’s ten largest mature economies to see where they stand in the process of deleveraging. We pay particular attention to the experience and outlook for the United States, the United Kingdom, and Spain, a set of countries that covers a broad range of deleveraging and growth challenges.

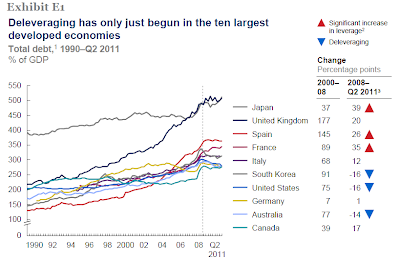

Deleveraging Only Just Begun

1 Includes all loans and fixed-income securities of households, corporations, financial institutions, and government.

2 Defined as an increase of 25 percentage points or more.

3 Or latest available.

The United States: A light at the end of the tunnel

Since the end of 2008, all categories of US private-sector debt have fallen relative to GDP. Financial-sector debt has declined from $8 trillion to $6.1 trillion and stands at 40 percent of GDP, the same as in 2000. Nonfinancial corporations have also reduced their debt relative to GDP, and US household debt has fallen by $584 billion, or a 15 percentage-point reduction relative to disposable income. Two-thirds of household debt reduction is due to defaults on home loans and consumer debt. With $254 billion of mortgages still in the foreclosure pipeline, the United States could see several more percentage points of household deleveraging in the months and years ahead as the foreclosure process continues.

[Mish Note: notice the key phrase "months and years ahead"]

Even when US consumers finish deleveraging, however, they probably won’t be as powerful an engine of global growth as they were before the crisis. One reason is that they will no longer have easy access to the equity in their homes to use for consumption. From 2003 to 2007, US households took out $2.2 trillion in home equity loans and cash-out refinancing, about one-fifth of which went to fund consumption.

Without the extra purchasing that this home equity extraction enabled, we calculate that consumer spending would have grown about 2 percent annually during the boom, rather than the roughly 3 percent recorded. This “steady state” consumption growth of 2 percent a year is similar to the annualized rate in the third quarter of 2011.

US government debt has continued to grow because of the costs of the crisis and the recession. Furthermore, because the United States entered the financial crisis with large deficits, public debt has reached its highest level—80 percent of GDP in the second quarter of 2011—since World War II.

The next phase of deleveraging, in which the government begins reducing debt, will require difficult political choices that policy makers have thus far been unable to make.

Not only that, but growth assumptions remain absurdly high as do earnings forecasts.

The McKinsey study is certainly supportive of my employment thesis: Fundamental and Mathematical Case for Structurally High Unemployment for a Decade; Shrinking Job Opportunities and the Jobs Gap; The Real Employment Situation

Moreover, and importantly, risks are all skewed to the downside because the European recession is going to prove to be a major disaster as noted in Italy Faces 2-Year Recession says IMF; European Recession Neither Mild Nor Short

Spotlight on UK and Spain

10 Largest Economies Composition of DebtNote how Spain was massively skewered by the ECB's "one size fits Germany" interest rate policy. That structural problem remains in spite of all the can kicking by the US and ECB with lending schemes and the LTRO.

1 Includes all loans and fixed-income securities of households, corporations, financial institutions, and government.

2 Q1 2011 data.

UK household debt, in absolute terms, has increased slightly since 2008. Unlike in the United States, where defaults and foreclosures account for the majority of household debt reduction, UK banks have been active in granting forbearance to troubled borrowers, and this may have prevented or deferred many foreclosures. This may obscure the extent of the mortgage debt problem. The Bank of England estimates that up to 12 percent of home loans are in a forbearance process. Another 2 percent are delinquent.

Overall, this may mean that the UK has a similar level of mortgages in some degree of difficulty as in the United States. Moreover, around two-thirds of UK mortgages have floating interest rates, which may create distress if interest rates rise—particularly since UK household debt service payments are already one-third higher than in the United States.

Spain: The long road ahead

The global credit boom accelerated growth in Spain, a country that was already among the fastest-growing economies in Europe. With the launch of the euro in 1999, Spain’s interest rates fell by 40 percent as they converged with rates of other eurozone countries. That helped spark a real estate boom that ultimately created 5 million new housing units over a period when the number of households expanded by 2.5 million. Corporations dramatically increased borrowing as well.

As in the United Kingdom, deleveraging is proceeding slowly. Spain’s total debt rose from 337 percent of GDP in 2008 to 363 percent in mid-2011, due to rapidly growing government debt. Outstanding household debt relative to disposable income has declined just 6 percentage points. Spain also has unusually high levels of corporate debt: the ratio of debt to national output of Spanish nonfinancial firms is 20 percent higher than that of French and UK nonfinancial firms, twice that of US firms, and three times that of German companies. Part of the reason for Spain’s high corporate debt is its large commercial real estate sector, but we find that corporate debt across other industries is higher in Spain than in other countries. Spain’s financial sector faces continuing troubles as well: the Bank of Spain estimates that as many as half of loans for real estate development could be in trouble.

Spain has fewer policy options to revive growth than the United Kingdom and the United States. As a member of the eurozone, it cannot take on more public debt to stimulate growth, nor can it depreciate its currency to bolster its exports. That leaves restoring business confidence and undertaking structural reforms to improve competitiveness and productivity as the most important steps Spain can take. Its new government, elected in late 2011, is putting forth policy proposals to stabilize the banking sector and spur growth in the private sector.

Let's return to the report for one more chart from the report.

US Household Debt Ratios

There are a lot of optimistic assumptions in that report. The above chart highlights one of the biggest assumptions.

Certainly one can make a case that the change from single-household worker families to dual-household worker families (both husband and wife working), accounts for the rise is sustainable debt loads from 1955 to 1985.

How much of the rest is sustainable? I suggest little to none of it is. The stock market boom of the 90's followed by housing bubble in the 2000's is what made families "feel" wealthy.

Negative Stock Market Returns for another Decade?

With global growth slowing, coupled with an enormous change in boomer demographics, combined with massive amounts of deleveraging still to come in the top 10 economies, the likelihood the stock market puts in another sustainable boom as it did in the 90's is highly unlikely. When households feel wealthy they are apt to take on more debt.

In a debt deleveraging cycle, not only does feeling wealthy go away, so does the likelihood of strong returns in the stock market. Indeed, I have made the case for Negative Returns for Another Decade

- Negative Annualized Stock Market Returns for the Next 10 Years or Longer? It's Far More Likely Than You Think

- Another "Lost Decade" Coming Up; Boomer Retirement Headwinds; P/E Expansion and Contraction Demographic Model; Negative Returns for a Decade Revisited

- Value Restoration Project: Stock Market Valuations and Trends Over Time

For the sake of argument let's assume an optimistic case of 4-5% annualized returns for another decade. Is that enough to keep that household debt trend intact?

Of course not. The idea the trendline itself should go up over time is complete silliness unless there is a structural change as there was in the 60's and 70's when women went to work en masse.

Nonetheless, the McKinsey Global Institute report is well worth a look in entirety. Click on the first link at the top for an opportunity to download the full 64-page report.

Obvious flaws aside, the report is a great read containing a wealth of information on debt levels of countries and what has been done to address the issues so far.

Mike "Mish" Shedlock

http://globaleconomicanalysis.blogspot.com

Click Here To Scroll Thru My Recent Post List